Shaping the Future of Technology

Electrical and computer engineering extends from the nanoscale level of integrated electronics to gigantic power grids; from single-transistor devices to networks comprising a billion nodes. Our students discover and apply new technologies and innovations in our three nationally-ranked academic degree programs.

Our Programs

- Minor

- B.S.

- M.Eng.On Campus

- M.Eng.Distance Learning

- M.S.

- Ph.D.

-

Electrical and Computer Engineering

Focuses on developing electrical systems, from circuits to computers. Great for those interested in hardware, software, and advancing technology.

Strategic Areas of Research

-

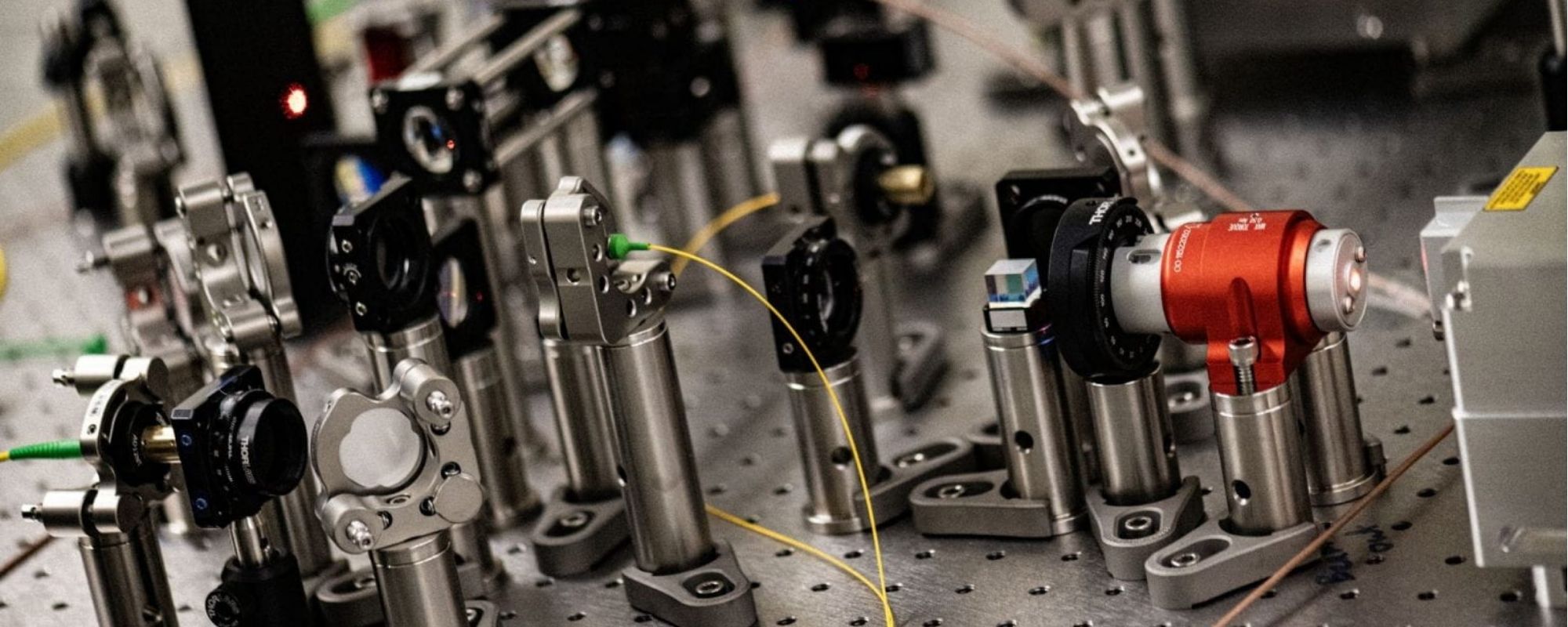

![Karan Mehta's Photonics and Quantum Electronics Group lab equipment]()

Bio-Electrical Engineering

Interfaces for sensing and actuation to help understand the physiological and pathological mechanisms of diseases, and enable advanced robotic interfaces in medicine.

-

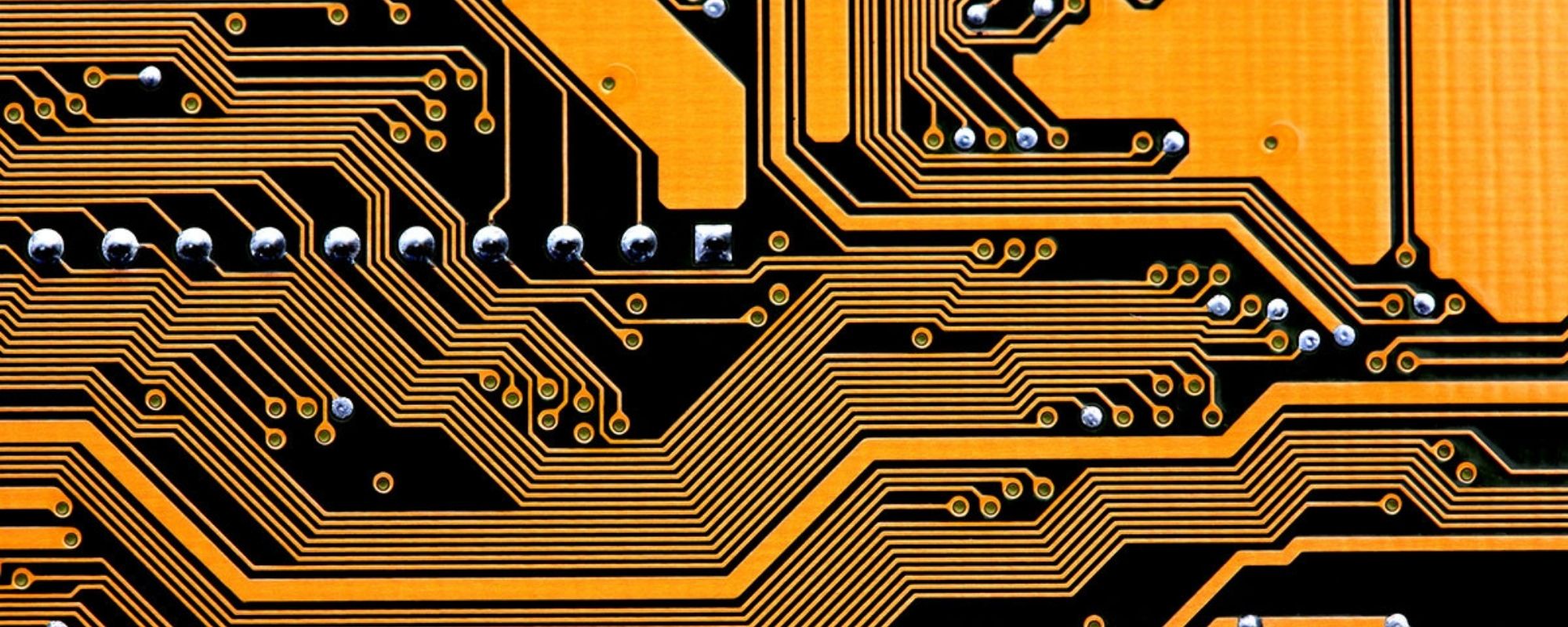

![Circuit board]()

Circuits and Electronic Systems

Analog and mixed signal circuits, RF transceivers, low power interfaces, power electronics and wireless power transfer, and many others.

-

![Blockchain graphic from the Statistical Signal Processing Lab of Vikram Krishnamurthy]()

Computer Engineering

Digital logic and VLSI design, computer architecture and organization, embedded systems and Internet of things, virtualization and operating systems, code generation and optimization, computer networks and data centers, electronic design automation or robotics.

-

![A drone in a strawberry field working on pollination. in Kirsten Petersen's lab]()

Information, Networks, and Decision Systems

The advancement of research and education in the information, learning, network and decision sciences.

-

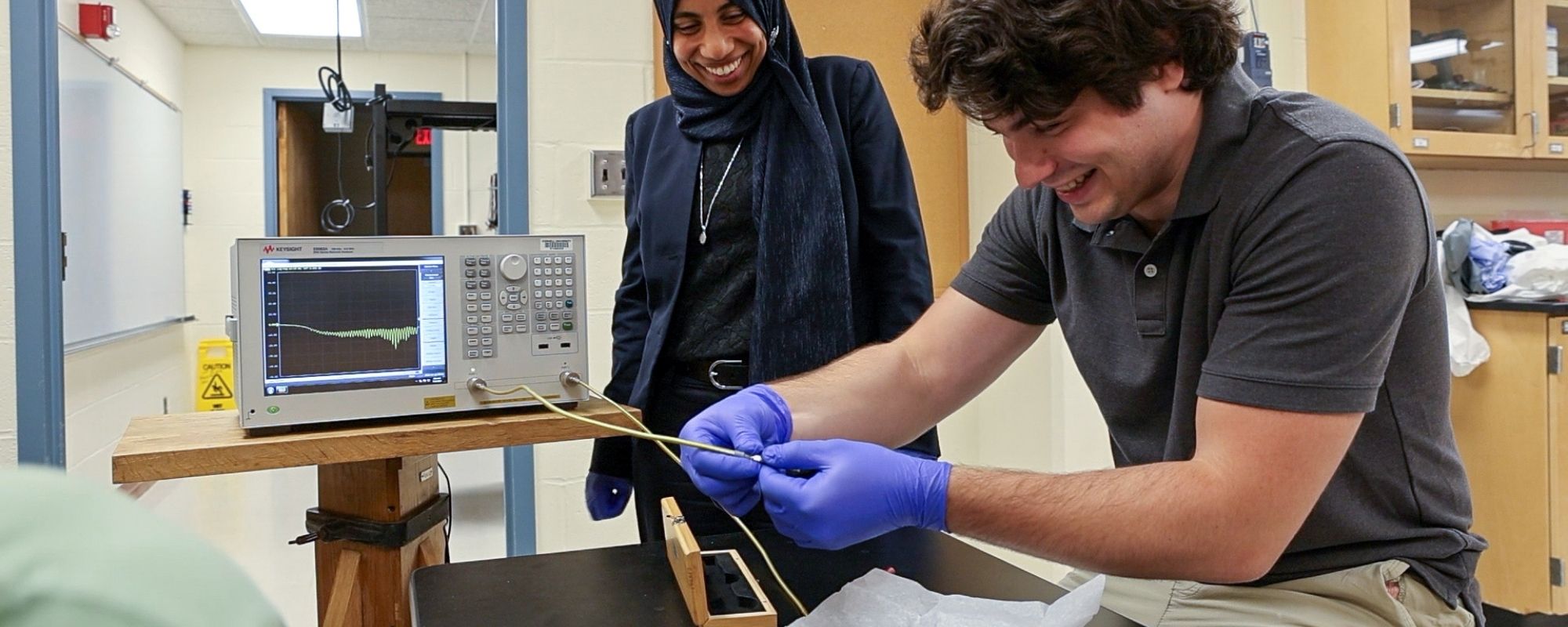

![Amal El-Ghazaly working with a student in her lab on magnetic sensors]()

Physical Electronics, Devices, and Plasma Science

Electronic and optical devices and materials, micro-electromechanical systems, acoustic and optical sensing and imaging, quantum control of individual atoms near absolute zero temperature, and experiments on high-energy plasmas at temperatures close to those at the center of the sun.

-

![Student showcasing their robot during the annual Electrical and Computer Engineering Robotics Showcase event]()

Robotics and Autonomy

Topics include swarm intelligence, embodied intelligence, autonomous construction, bio-cyber physical systems, human-swarm interaction, and soft robots.

News Highlights

-

Awards honor Cornell Engineering faculty for teaching, advising

Cornell Engineering honored the transformative impact of its faculty at the 2025 Fall Faculty Reception, recognizing this year’s Teaching and Advising Award winners for their outstanding commitment to student success.

-

New faculty Tianyi Chen is engineering AI to make smarter and balanced decisions

Tianyi Chen is pushing the boundaries of artificial intelligence by asking a pressing question: What if AI could be engineered not just to optimize for a single outcome, but to make smarter, more balanced decisions — much like humans do?

-

Expanded SPROUT Awards maintain engineering innovation momentum

From mapping the human gut-brain connection to creating safer cancer nanotherapies, the latest Expanded SPROUT Awards from Cornell Engineering are exploring breakthroughs in microbiome science, quantum materials and biomedical engineering.

-

Balancing the promise of health AI with its carbon costs

The health care industry is increasingly relying on AI – in responding to patient queries, for example – and a new Cornell study shows how decision-makers can use real-world data to build sustainability into new systems.

-

Cornell showcases semiconductor leadership at 2025 SUPREME annual review

Cornell University hosted the 2025 SUPREME annual review, bringing together academia, industry, and government to advance next-generation semiconductor innovation and workforce development.